Jesse Lawrence Contributor

Jesse Lawrence has been in media and tech for 20 years. Prior to

TicketIQ, he worked at MediaMath and IAC. He started his career as a writer.

More posts by this contributor

Among the many myths that were laid low in 2018, perhaps none was as welcome to throngs of live event fans as the fantasy of the sold-out show. Indeed, as the ticket market has moved to adopt new technology the new-found transparency has had one prime victim: The Sellout.

The highest-profile debunking of the sellout in sports for 2018 came from Washington, DC.

Originally reported by the Washington Post, the Washington Redskins officially ended their decade-long season-ticket waitlist this June. Once claimed to be 200,000 fans deep, the reality of Redskins demand hadn’t been as rosy since the glory days of Riggins and Theisman. In 2018, the Redskins have been selling single game tickets like never before — even using the secondary market as a favorable point of comparison.

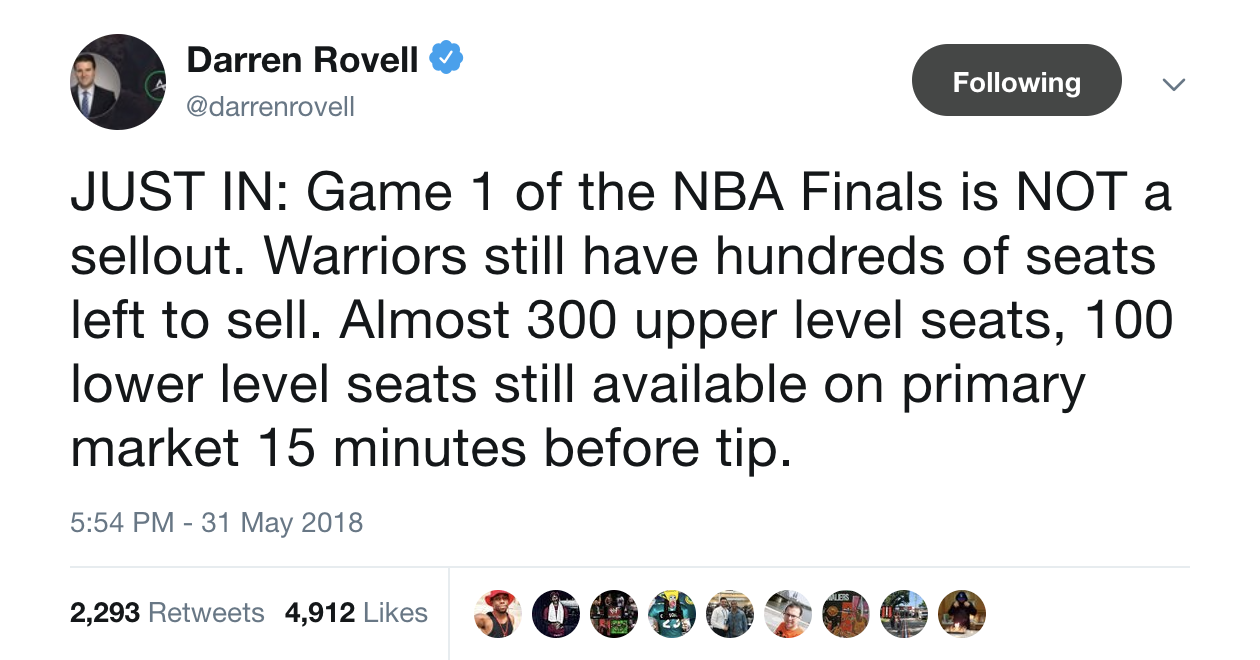

Other high-profile examples of this shift include the Golden State Warriors, who, despite selling out 100% of their regular season games, had hundreds of tickets available on for Game 1 of the NBA finals in the minutes before tip-off.

If the Redskins and Warriors signaled a shift away from the sellout era in sports, Taylor Swift’s Reputation tour did the same for music. Having wrapped up earlier this month, Reputation finished as the highest grossing US Tour in history, despite a flurry of articles lambasting the artist for not selling out many shows. Ironically, it turns out that the most important factor in her record-breaking success was exactly that: not selling out.

Rather than a lack of demand, these unsold tickets for high-profile events are the result of the latest trend in the ticketing industry — making sure you have tickets to sell when fans want to buy them. Anyone that has purchased tickets on the Internet knows that the most active buying window is in the days and hours leading up to an event.

Before the Internet, while this last-minute market existed, it was contained to street corners and run by local brokers. For most of the 20th century, managing this aftermarket was a job ticket owners were comfortable outsourcing. With it’s limitless reach and real-time distribution, however, Internet-based selling changed their comfort level dramatically, by removing the ticket owner from the supply chain and costing them billions in margin. It also created a product category that became one of the worst, if not the worst, on the Internet.

If not for the universal appeal of live events, ticketing as a product would have died with Pets.com. Instead, teams, artists and promoters became the poster children for the Internet’s power to disrupt. The response from many ticket owners was to simply to hang up a ‘Sold Out’ sign at the box office in the weeks, days and hours before the game — one that is just now starting to be taken down.

Photo courtesy of Getty Images

To understand why that happened, it’s important to recognize that when the Internet took off, teams were principally in the season-ticket business, while artists and promoters were in the record-selling business. Selling last-minute, ‘on-demand’ tickets simply wasn’t a focus. The Internet, however, turned that secondary market niche into a product category worth $10 to $15 billion at it’s peak — two to three times the size of the primary market it was based on.

In order to compete in this always-on marketplace, ticketing technology has received billions of dollars of investment in the last decade, with the goal of making it more compatible with the Web itself. In the last two years, Ticketmaster, Seatgeek and Eventbrite have all announced ‘open platform’ models that make it as easy to sell tickets in places like Facebook and Youtube as it does in Stubhub.

In January, Ticketmaster and the NFL announced a new platform deal that, for the first time ever, allows teams and leagues to define their own distribution ecosystem. As one of the biggest destinations for ticket buying online, sites like Stubhub and my company, TicketIQ, have become direct-to-fan distribution channels in the new ticketing marketplace.

(AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

Before we singlehandedly credit technology for killing the sell out, it’s worth asking whether the decline in sellouts is simply the result of exorbitant ticket prices and increased competition for consumer attention. While there’s no question that it’s become harder to get people off of their couches for average events, the robust growth of the experience economy suggests the opposite trend.

According to a December 2017 McKinsey report, millennials spend 60% more on live experiences than GenXers — all in search of not only genuine connection, but also fresh social-media content. For the Reputation tour specifically, last-minute tickets on the secondary market were actually 35% cheaper than 1989 tour, which made buying tickets day-of the event more affordable than ever.

As for the Redskins, while their 2018 season hasn’t turned out as they’d hoped, at the box office, they’ve set themselves up for success in the years to come. When demand spikes, whether as the result of a new stadium or a championship run, they’ll benefit directly and handsomely. As a point of reference for what kind of profit they might expect, the Financial Times reported that Taylor Swift’s per-show gross for Reputation increased by $1.4 million, including two dates in July at Fedex Field, home of the Redskins.

In “Look what you Made Me Do” the sixth song on the Reputation album, Taylor Swift sings about past “games”, “a tilted stage” and “unfair disadvantage”, for which she now seeks retribution. As a statement about her artistic and commercial stature, it’s clear she no longer wants to play nice. In addition to a jab at her artistic nemesis, Kanye West, it also reads like a farewell to the ticket market of old that has frustrated consumers for almost two decades.

Despite claims that she sold out her fans to achieve Reputation’s record-breaking success, the numbers mean that it’s a model we’ll be seeing much more of in the years to come. Regardless of how you feel about her forcing fans to Buy, Like and Watch to get their place in line for tickets, the good news for the ticket market overall is that it was her decision to make.

from TechCrunch https://tcrn.ch/2F2kvt5